Soaps are cleaning agents that are usually made by reacting alkali (e.g., sodium hydroxide) with naturally occurring fat or fatty acids. The reaction produces sodium salts of these fatty acids, which improve the cleaning process by making water better able to lift away greasy stains from skin, hair, clothes, and just about anything else. As a substance that has helped clean bodies as well as possessions, soap has been remarkably useful.

History of Soap

The discovery of soap predates recorded history, going back perhaps as far as six thousand years. Excavations of ancient Babylon uncovered cylinders with inscriptions for making soap around 2800 B.C.E. Later records from ancient Egypt (c. 1500 B.C.E. ) describe how animal and vegetable oils were combined with alkaline salts to make soap.

According to Roman legend, soap got its name from Mount Sapo, where animals were sacrificed. Rain would wash the fat from the sacrificed animals along with alkaline wooden ashes from the sacrificial fires into the Tiber River, where people found the mixture helped clean clothes. This recipe for making soap was relatively unchanged for centuries, with American colonists collecting and cooking down animal tallow (rendered fat) and then mixing it with an alkali potash solution obtained from the accumulated hardwood ashes of their winter fires. Similarly, Europeans made something known as castile soap using olive oil. Only since the mid-nineteenth century has the process become commercialized and soap become widely available at the local market.

Chemistry of Soap

The basic structure of all soaps is essentially the same, consisting of a long hydrophobic (water-fearing) hydrocarbon "tail" and a hydrophilic (waterloving) anionic "head":

CH 3 CH 2 CH 2 CH 2 CH 2 CH 2 CH 2 CH 2 CH 2 CH 2 CH 2 CH 2 CH 2 CH 2 CH 2 COO − or CH 3 (CH 2 ) n COO −

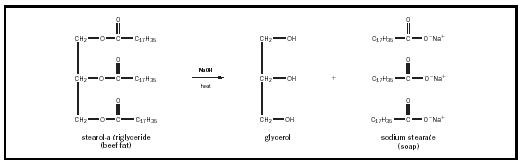

The length of the hydrocarbon chain ("n") varies with the type of fat or oil but is usually quite long. The anionic charge on the carboxylate head is usually balanced by either a positively charged potassium (K + ) or sodium (Na + ) cation. In making soap, triglycerides in fat or oils are heated in the presence of a strong alkali base such as sodium hydroxide, producing three molecules of soap for every molecule of glycerol. This process is called saponification and is illustrated in Figure 1.

Like synthetic detergents, soaps are "surface active" substances ( surfactants ) and as such make water better at cleaning surfaces. Water, although a good general solvent, is unfortunately also a substance with a very high surface tension. Because of this, water molecules generally prefer to stay together rather than to wet other surfaces. Surfactants work by reducing the surface tension of water, allowing the water molecules to better wet the surface and thus increase water's ability to dissolve dirty, oily stains.

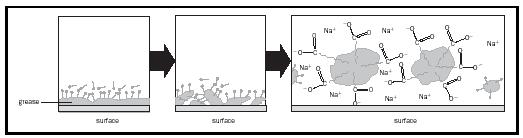

In studying how soap works, it is useful to consider a general rule of nature: "like dissolves like." The nonpolar hydrophobic tails of soap are lipophilic ("oil-loving") and so will embed into the grease and oils that help dirt and stains adhere to surfaces. The hydrophilic heads, however, remain surrounded by the water molecules to which they are attracted. As more and more soap molecules embed into a greasy stain, they eventually surround and isolate little particles of the grease and form structures called micelles that are lifted into solution. In a micelle, the tails of the soap molecules are oriented toward and into the grease, while the heads face outward into the water, resulting in an emulsion of soapy grease particles suspended in the water.

With agitation, the micelles are dispersed into the water and removed from the previously dirty surface. In essence, soap molecules partially dissolve the greasy stain to form the emulsion that is kept suspended in water until it can be rinsed away (see Figure 2).

As good as soaps are, they are not perfect. For example, they do not work well in hard water containing calcium and magnesium ions, because the calcium and magnesium salts of soap are insoluble; they tend to bind to the calcium and magnesium ions, eventually precipitating and falling out of solution. In doing so, soaps actually dirty the surfaces they were designed to clean. Thus soaps have been largely replaced in modern cleaning solutions by synthetic detergents that have a sulfonate (R-SO 3 − ) group instead of the carboxylate head (R-COO − ). Sulfonate detergents tend not to precipitate with calcium or magnesium ions and are generally more soluble in water.

Uses of Soap

Although the popularity of soap has declined due to superior detergents, one of the major uses of animal tallow is still for making soap, just as it was in years past. Beyond its cleaning ability, soap has been used in other applications. For example, certain soaps can be mixed with gasoline to produce gelatinous napalm, a substance that combusts more slowly than pure gasoline when ignited or exploded in warfare. Soaps are also used in "canned heat," a commercialized mixture of soap and alcohol that can be ignited and used to cook foods or provide warmth. Overall, soap is a remarkably useful substance, just as it has been for thousands of years.

David A. Dobberpuhl